Capital mobilisation query leads power plan analysis

Capital mobilisation query leads power plan analysis

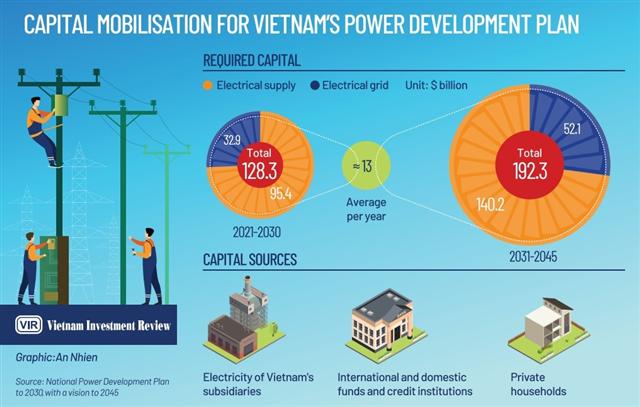

The third draft of the National Power Development Plan 8 (PDP8) is 843 pages thick but only nine of these cover financial issues, with an average mobilisation of $13 billion per year until 2045. The capital is allocated to power generation, transmission lines for gas, and wind power sources, among others.

Capital mobilisation query leads power plan analysis

|

The draft, however, does not mention where to mobilise capital from, at home or from abroad, while possible solutions to this questions are all burdened with administrative procedures.

“The new PDP8 will be better than its predecessor,” commented Ngo Duc Lam, former deputy director of the Ministry of Industry and Trade’s Institute of Energy.

For the first time, the PDP8 closely adheres to the national development and energy development strategies – the previous plan could stick to Resolution No.55-NQ/TW of the Politburo on the orientation of the National Energy Development Strategy of Vietnam to 2030, with a vision to 2045.

The previous master plan, implemented from 2015 to 2018, failed and could not mobilise enough capital according to Lam. He said that, in mobilising capital for the PDP8, it is necessary to review its predecessor.

“Firstly, the assessment of the socioeconomic situation was not carried out properly, with GDP being forecast too high, so the first three years have to be adjusted which can be quite expensive. Next, the electricity development trend is not in line with the rest of the world. Climate change is making the world switch to renewable energy, but Vietnam is moving in the opposite direction, developing coal-fired power at a higher level,” Lam criticised.

Lam found that borrowing from credit institutions to implement energy projects is also very difficult because many of them introduce technical barriers to environmental protection when lending to power projects. “Thus, the financing for energy investments continues to be a challenge for regulators if there is no change,” Lam said.

Sufficient structures

Pham Xuan Hoe, former deputy director of the Banking Strategy Institute under the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) said, “It will be very difficult for Vietnam to mobilise capital as outlined in the PDP8.” Firstly, divesting capital for coal power of all 146 international financial institutions is very difficult, although Japan’s Mitsubishi Corporation has decided to withdraw from the Vinh Tan 3 thermal power plant project in the south-central province of Binh Thuan, where it holds 49 per cent of the shares.

Secondly, if capital is borrowed from China, it is accompanied by loan conditions as well as bonds for government guarantees at high prices. The most obvious experience is that Laos had to cede a partial concession of the national power transmission system to China.

“Here, we do not take into account the structure of capital sources, and how much will be mobilised domestically and abroad. If Vietnam develops six more coal-fired power plants as outlined in new draft, the country will surely have to borrow more from China,” Hoe said.

Third is the weak international commitments of the Vietnamese banking system to global standards of governance and environmental and social responsibility. Therefore, local banks certainly cannot lend more to the coal sector in the context of increasing international pressure on banks. Thus, capital for large-scale coal-fired power projects such as Nhon Trach 2 in the central province of Quang Binh, which amounts to VND48 trillion ($2.81 billion), will be complex.

“Policy risks in Vietnam are also high and have shown to be unstable, and the commitment to foreign investors could be better,” Hoe said. “For example, in the solar sector, Vietnam only offered a feed-in tariff for more than a year, and then switched to bidding processes again. Therefore, many investors are reviewing the risks in laid out policies. Unstable commitments certainly cannot mobilise capital.”

Next, the medium- and long-term capital supply of the Vietnamese banking system remains very low, at just over 20 per cent with high interest rates and minimum loans above 10 per cent per year. Furthermore, Vietnam’s green bond market is almost empty. In order to develop a renewable energy market, such as wind or solar power, a green bond market must be developed. This concept was discussed by the government, but so far green public investment and expenditures are still “very fuzzy” in the fiscal balance of the Ministry of Finance (MoF), argued Hoe. Finally, Vietnam has no national agency to access international sources of green growth, especially for renewable energy.

Resolution 55 not concretised

The new plan is being promoted for early submission to the government. Hoe said that the plan “has been calculated very carefully”. If capital is mobilised from state corporations, it will amount to only about $3 billion per year, because all these groups have debt ratios of over 2 per cent. Currently, the debt ratio of Electricity of Vietnam (EVN) has reached 2.25 per cent. Another $4 billion will be mobilised from the population and $4 billion from the domestic businesses. If there are good policies, Vietnam can also mobilise $6-7 billion per year from foreign direct investment.

Two important directions of Resolution 55 that cover green public expenditures and the green fiscal year have not been specified in Chapter 14 of the PDP8. “Winning green public investment for renewable energies, especially in transmission, should be clearly stated in Chapter 14 of the PDP8,” added Hoe.

Vietnam’s green finance policy, he said, is so far “at an incentive level”. In the 5-year plan, “the MoF has never balanced a single source of capital for green public investment.”

Resolution 55 states that green credit policies must be concretised to support investments in renewable energies. But when EVN stopped receiving connection requests and signed a power purchase agreement for rooftop solar systems developed after December 31, banks, despite their very good retail sales, immediately stopped providing loans. According to Hoe, such a plan should be stated in Chapter 14, with the SBV directing the banking system to promote retail credits for renewable energy, using lower refinancing interest rates for credit loan records, and reducing the required reserve ratio for loans.