Central bank bewildered by impossible credit goal triad

Central bank bewildered by impossible credit goal triad

The State Bank of Vietnam lowered its interest rates last week, joining the global easing bandwagon in a bid to cushion the economic fallout stemming from the pandemic.

Prof. Dr. Andreas Stoffers, Munich - is a former banker in Germany and Vietnam and professor at SDI Munich University, and now country director Vietnam for the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom.

|

After several months of the worldwide fight against COVID-19, the serious economic consequences for globally networked economies are now becoming increasingly apparent.

All over the world, from Germany and the United States, in Great Britain and Japan, to South Korea and Vietnam, economists and politicians are considering how best to deal with the “crisis after the crisis” in order to mitigate the economic and social consequences of the pandemic and the measures taken because of it.

Vietnam is following an interesting path which differs in parts from that of other nations but in parts also resembles it. The State Bank of Vietnam’s (SBV) policy plays an essential role in this respect. Unlike the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve, which have already lowered their key interest rates to zero since 2016 and 2020, respectively, the SBV still has room to manoeuvre here.

The SBV’s interest rate cuts are easing the weight from the shoulders of commercial banks

|

Meanwhile, it is for the second time that the SBV has reduced interest rates in response to COVID-19.

The first time was on March 17 when the interest rates were lowered at the maximum of 1 per cent point. The most important changes according to the recent decisions (No.918 and 920/QD-NHNN) are:

* The refinancing interest rate will be reduced from 5.0 to 4.5 per cent per year;

* The rediscount interest rate will be reduced from 3.5 to 3.0 per cent per year;

* The overnight lending interest rate in inter-bank electronic payment and lending to compensate for capital shortages in clearing from the SBV to banks will decrease from 6.0 to 5.5 per cent per year;

* The maximum short-term lending interest rate in VND of credit institutions for borrowers will decrease from 5.5 to 5.0 per cent per year;

* The maximum short-term loan interest rate in VND of people’s credit funds and micro-financial institutions for these funds will drop from 6.5 to 6 per cent per year.

|

Compared to the first reduction, the new measures are more comprehensive and definitely more targeted at businesses and banks in order to fight the recession. As far as commercial banks are concerned, the new interest rate cuts reduce the burden of liquidity on banks due to the impacts of COVID-19 and the falling of profits. With a lower refinancing interest rate, rediscount interest rate, and interest rate for deposits, banks can better support companies during COVID-19 and give more loans, which will result in higher yields for the banks.

Regarding corporates, the interest rates reduction allows them to lower capital costs. This is definitely valuable and needed in times when around 35,000 business in the first quarter of 2020 ceased operations and the severe economic impacts of the pandemic will be even worse in the second quarter, with the US, the EU, and Vietnam’s other trade and investment partners still struggling. The early signal from 4,000 corporations ceasing operations in Hanoi alone until April are a warning, especially in combination with the 26 per cent on-year slump in total revenue from retail goods and services in April. Thus, the SBV’s measures can be considered as an essential move to save banks and companies. At the same time, it is absolutely suitable to the current economic situation, when the consumer price index in April decreased 1.54 per cent on-month, the lowest level in 2016-2020.

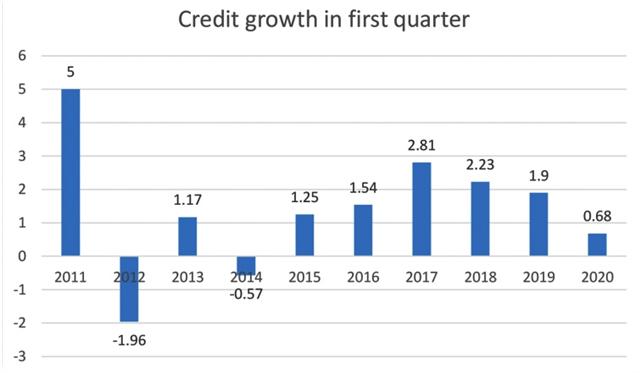

Moreover, it is alarming that more than 41,000 companies stopped operating in the first four months. The SBV’s measures also help to boost credit growth, which in the first quarter experienced the lowest levels in six years.

It is obvious that the low credit growth in this quarter is threatening Vietnam’s economic development. The government’s credit growth target of 16-18 per cent in 2020 will be difficult to maintain in case the current situation persists. Additionally, the lack of capital is a serious issue for 45 per cent of enterprises in Vietnam, according to the Ministry of Planning and Investment. These companies need to be saved in the future while banks accept to loose a great deal of profit to support companies along with the SBV’s first support wave.

The low credit growth is definitely bad for economies in crisis. But then, Vietnam’s high credit growth in 2007 and 2009 (54 and 36 per cent) could pose a risk of hazardous levels of inflation, financial bubble, bad debts, and so on. Therefore, the government should, on the one hand, support credit growth while on the other hand carefully ensuring that it does not exceed 18 per cent this year, in order to minimise negative side effects. However, besides the opportunities, several risks have to be considered, too. First, bad debts are likely to increase in the second quarter, especially when enterprises find it more easy to approach capital. Currently, due to the pandemic, VND19.2 quadrillion ($834.78 billion), equivalent to 23 per cent, of outstanding debt is likely to turn into bad debt. Second, the credit growth quotas are set at 16-18 per cent for this year, which definitely puts a burden on the SBV and commercial banks as economic stability has been disrupted by COVID-19. Rather than that, the SBV should permit credit activities to go on a demand-supply basis while maintaining the stability of banks through capital adequacy ratio (CAR). The current situations triggers an impossible triad, in which it is difficult to reach all three relevant targets to ensure stability. These targets include crafting support policy to rescue enterprises, ensuring banks’ profit, and maintaining CAR in the banking sector.

If the SBV chose a support policy and bank profit (targets 1 and 2), this probably leads banks into temptation to allocate sub-prime loans, which entails the danger of souring into toxic loans and a soaring non-performing loan ratio. If the SBV eyes bank profits and the stability of the banking sector (targets 2 and 3), the financial institutions would start focusing on making as much money as possible form loans by increasing the margins, which could kill companies who are losing the capacity to meet principal payments. If the SBV focuses on CAR and support policies (targets 1 and 3), banks could not make money due to the lack of money for credit.

That is a painful choice. The third way (CAR and support policy) might be suitable at this moment to save companies from bankruptcy but there is also a need to encourage banks to increase their profits from service activities. The latter is not so easy, because – as a matter of fact – currently, most bank profits come from margins. Vietnam’s monetary measures described here are an important step in the right direction. They will help to mitigate the emerging negative economic consequences of the pandemic. At the same time, they will leave room for further interventions, should they become necessary.

It will be important, following this emergency aid, to return to the old path of liberal economic policy, a path which made Vietnam so successful in the years following doi moi in 1986. Vietnam could make full use of its free trade agreements, especially the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement, to revitalise trade, and further develop its industry.