Improved business environment is the key to FDI not tax and land incentives

Improved business environment is the key to FDI not tax and land incentives

ASEAN countries need to choose between recovery based on wasteful competition for investment or coordination, cooperation, and joint hands to generate sustainable tax revenue to spend on health, education, and other public goods that are essential to fight poverty and inequality.

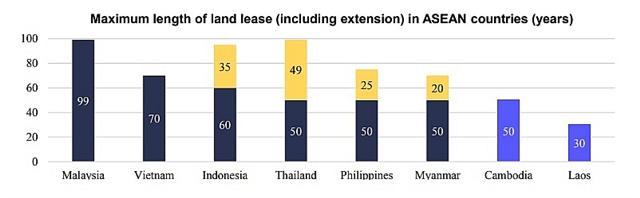

Maximum length of land lease (including extension) in ASEAN countries (years)

|

COVID-19 is posing enormous challenges to the ASEAN region. In addition to the health and economic crisis, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows into developing Asian countries are predicted to decrease by 30-40 per cent and tax revenues are collapsing.

The workshop “Towards sustainable FDI attraction in ASEAN: Business environment is the key driver” in Hanoi on November 11 shared findings from a recent research by Oxfam and partners, emphasising the importance of coordinated efforts by ASEAN governments to stop redundant incentive packages and prioritise enhancing the business environment for investment promotion.

Before the pandemic, countries in the ASEAN region were competing with one another in a race to the bottom by offering excessive tax and non-tax incentives to attract FDI without real value generation. Instead of building a business environment that could be the key determinant in FDI location decisions, governments in the region have adopted wasteful and aggressive tax policies that have only benefited large foreign companies, according to recent research by Oxfam and partners. In response to the pandemic and to promote sustainable development, ASEAN needs to avoid falling into the trap of needless competition.

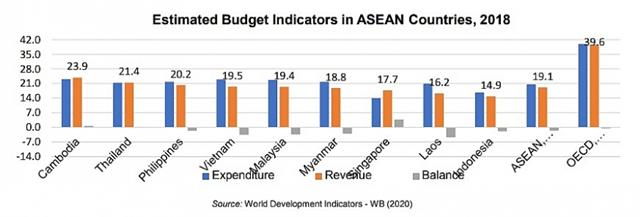

Over the last 10 years, countries in the ASEAN region have been competing in reducing their corporate income tax (CIT) rates and offering aggressive tax incentives to foreign multinational corporations. As a result, ASEAN’s average CIT rate has declined from 25.1 per cent in 2010 to 21.7 per cent in 2020. In addition to CIT cuts, the use of other enormous profit-based incentives to attract FDI, like tax holidays, are prevalent in ASEAN countries.

The costs of redundant fiscal incentives can exceed the benefits of additional FDI, undermining national tax revenues without evidence of return. Lost budget revenue due to CIT incentives was estimated to be 6 per cent of GDP in Cambodia and 1 per cent in Vietnam and the Philippines.

Besides tax incentives, the use of non-tax incentives has been widespread among ASEAN countries and exacerbated the race to the bottom in the region. The competition in providing non-tax incentives is centred on land incentives. Long-term land lease is available in all ASEAN countries and Thailand even allows foreign investors to own land in some special cases. Vietnam and Laos provide rent exemption or reduction to investment projects in hard-hit regions or in promoted business lines.

This competition in land incentives among ASEAN countries is subsequently enlarging socioeconomic inequality, and the obscure mechanisms of granting land incentives in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar are opening up opportunities for corruption and rent-seeking.

“While business should be a race to the top, competition in tax and land incentives is a race to the bottom. The granting of land incentives, particularly the extension of leasehold terms, lacks transparency which could increase the risks of corruption,” said Pham Van Long, a researcher at the Vietnam Institute for Economics and Policy Research (VEPR).

The ASEAN region is experiencing unprecedented economic inequality, as some countries still have the highest poverty levels in the world and most countries in the region are failing to invest sufficiently in essential public services. COVID-19 will only amplify poverty and inequality due to the differences in the ability to secure jobs and in the levels of access to healthcare. Myanmar, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines are among the top 20 countries seeing the largest increases in poverty headcount ratios over the world due to COVID-19.

Unnecessary tax and non-tax incentives affect countries’ capacity to mobilise domestic revenue and therefore spending levels on public essential services to face the pandemic by fighting poverty and reducing inequality. “The absurd situation is that they may not necessarily determine the level of FDI inflows as many policymakers often think,” said the representative of VEPR.

|

Many researches find that business environment indicators are key determinants of FDI location decisions, such as economic stability, political stability, local markets, transparency of legal framework, labour quality, the quality of infrastructure, particularly the density of high-quality roads, among others.

The report, building upon comparative experiences of other regions and exploring case studies from ASEAN, makes five recommendations for ASEAN countries to act cohesively: set up black and whitelists of tax incentives clarifying harmful taxation; stop the competition in providing site incentives; agree on a common minimum tax standard; establish rules for the good governance of investment incentives; and agree on a list of business environment factors that are key to attracting FDI.

“ASEAN countries should join hands in the fighting against poverty for millions of lives in the region. It’s high time to realise that tax incentives and non-tax incentives are deepening social and economic inequalities, and that is not the key to sustainable foreign investments. Every government needs sustainable revenue to spend on health and education services and other public goods which are essential to fight poverty and inequalities; so, all the member states need to unite to prioritise enhancing business environment instead of giving away ineffective incentives,” said Mustafa Talpur, Regional Inequality Campaign lead, Oxfam in Asia.

| In 1996, competing to lure investment from General Motors, the Philippines offered a CIT exemption for eight years and Thailand offered a similar exemption with an additional amount equivalent to $15 million. In addition, in 2001, to appeal for investment from Canon, Vietnam provided an exemption for 10 years, but the Philippines matched Vietnam by giving an exemption from 8-12 years. Finally, in 2014, in order to entice Samsung, Indonesia offered an exemption for 10 years while Vietnam offered one for 15 years. |