Balancing act required for efficiency of ODA in Vietnam

Balancing act required for efficiency of ODA in Vietnam

For nearly three decades, Vietnam has made use of official development assistance from foreign partners, thereby accelerating socioeconomic development in areas like infrastructure, science and technology, and human resources. However, strict regulations, high interest rates, and other constraints are some of the reason why ministries are beginning to look for domestic alternatives.

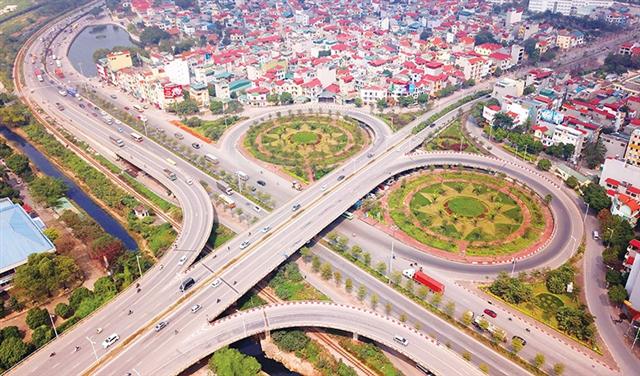

illustration photo

|

The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) announced that it would pay back oficial development assistance (ODA) amounting to VND1.8 trillion ($78 million) since it “has no further use for it”, according to MARD Deputy Minister Nguyen Hoang Hiep.

In 2017, the MARD signed project assistance but ended not using the entire amount until October 2019. The VND1.8 trillion is the sum of surplus from several projects which will be completed by the end of the year and no longer need more capital.

“We have been implementing these projects but were only using parts of the assigned capital,” Hiep stated, adding that he believed the return of the surplus amount would not affect the ODA contract signed three years ago.

However, the MARD also stated that there is still a need for such assistance for the 2021-2025 period, in which the ministry already planned with around VND144 trillion ($626 million) for the first 515 projects.

A report from the Ministry of Finance (MoF) on August 26 recorded nine ministries that requested to return a total of VND3.7 trillion ($160 million), equalling 32 per cent of originally assigned ODA. The MARD’s proposed repayment accounts for nearly 50 per cent of that, followed by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment’s proposal to return VND330 billion ($14.5 million) and transfer foreign capital to other ministries and localities.

Additionally, the MoF also received an inquiry from the Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences and Technology to cancel 75 per cent of the agreed VND400 billion ($17.5 million) that was arranged for a project with the University of Science and Technology of Hanoi due to slow disbursement. Meanwhile, the Management Authority of Hoa Lac Hi-tech Park proposed to reduce the VND50 billion ($2.2 million) foreign capital assigned to its infrastructure development project and instead supplement others in need.

“In Vietnam’s economic history, there has never been any request to cancel, reduce, or transfer ODA funds,” remarked Dr. Vo Dai Luoc, general director of the Vietnam Asia-Pacific Economic Centre. “As the government has been tightening regulations on managing and using such funds, it seems smarter to return the unused ODA capital.”

Donors’ requirements

Vietnam began receiving ODA funds from the international community in 1993, which helped to achieve its remarkable socioeconomic development throughout the decades. However, since it became a middle-income country in 2010, aid sources gradually diminished while lending rates were rising.

For instance, Japan’s ODA into Vietnam has increasingly become stricter and expensive. As such, lending rates for loans during the fiscal year 2018 rose 0.3 per cent from October 1, 2017. Moreover, preferential rates applicable to loans also rose from 0.3 to 1 per cent per year. Japan began requiring to set the salary level of advisors for financial loan projects at about $30,000 per month per person, not including allowances – 20-25 per cent higher than average salaries of foreign ODA consultants.

Relations between Vietnam and foreign donors have changed as the former has hit a higher development status than previously. This is believed to diplomatically allow for more binding cooperation in Vietnam’s ODA reception and use. However, economically seen, ODA remains funding from more developed economies, not unconditional aid.

According to Luoc, donors are aware of a possible waste of ODA and, therefore, look at least for two minimum requirements – the benefit the donor gains must ultimately be larger on a national level than the invested money; and that businesses of the donor’s home country will want to benefit from ODA projects too. However, if both conditions are fulfilled, the recipient’s benefits are few.

In principle, the country receiving ODA has the right to use and administer the ODA capital at their discretion, but in practice this often merely results in the right to negotiate about procedures. Projects using ODA must then cover 90 per cent of its designing costs as well as the import of machines and equipment from the donor. In addition, the repayment of foreign debts, mostly in USD, is another factor negatively impacting the recipient country, which often has to pay significant surcharges. However, one of the most concerning factors about ODA projects is that some projects, especially in infrastructure, are prone to corruption and waste by both donors and recipients within the design and planning stages.

“In the context of the current global and domestic economic conditions, we should limit, or even completely refuse, the use of ODA,” Luoc said, adding that “the government’s move to tighten management and use of ODA was right as its disbursement is not the clear responsibility of one agency or individual but includes many levels. I think the government needs to define those responsibilities right from the start of each project.”

| Decree No.56/2020/ND-CP on the management and use of ODA emphasises the government’s standing that this type of capital should preferably be used for development spendings, not for recurrent expenditures. The decree also unifies the state’s view on management of ODA and concessional loans on the basis of ensuring capital efficiency and debt repayment abilities, as well as transparency and accountability for related policies. At the same time, the decree offers a framework to prevent corruption and mismanagement while using ODA according to the provisions of the law. |

Retaining importance

As soon as lending rates were on the rise, the Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI) warned of the limitations of ODA. In its report about the management and use of ODA and concessional loans for the 2018-2020 period, the MPI stated that Vietnam could fall into an ODA trap if it does not carefully consider all important factors, such as lending rates and capital arrangement fees that could be higher than commercial ones in the domestic market. Accordingly, the MPI advised the government for the 2021-2025 period to only make use of ODA capital for programmes and projects with a large enough scale to maximise efficiency and meet the development needs of the country.

For a while, ODA has played the role of channelling foreign currency mobilisation. However, according to the MPI’s assessment, ODA and concessional loans should only account for 30-50 per cent of a project’s investment and act as a primer or catalyst in addition to other capital sources. As such, Vietnam should prioritise their use in projects that directly promote sustainable growth and are capable of generating foreign currency income in the medium and long term.

Nonetheless, Vietnam’s promotion of ODA disbursement shows that this funding is still considered an important capital source in projects relating to infrastructure, science and technology, and human resources. According to the MoF, as of August 27, ODA disbursement of localities only reached about 22 per cent of the assigned estimate. However, the situation improved compared to June when it only hit about a mere 13 per cent. Vietnam is also starting to address more issues related to the slow disbursement of ODA capital, such as cutting administrative procedures and land clearance, and finding ways to facilitate the entrance of foreign experts amid battling the pandemic.

Of course, each locality has its reasons for the speed of ODA disbursement. Nguyen Doan Toan, Deputy Chairman of Hanoi People’s Committee, said that problems in policy adjustments and foreign loan arrangement have slowed down the disbursement in the capital this year. For instance, Hanoi has yet to complete the second urban railway project which includes the construction of the South Thanh Long-Tran Hung Dao section close to Hoan Kiem Lake as construction and bidding packages of the project were not yet disbursed.

|

Shimizu Akira - Chief representative, JICA Vietnam

It is important for the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) to maintain and expand its operations in Vietnam. In addition to the ODA loans to support infrastructure projects, JICA works with local partners to improve operational mechanisms and train required human resources. For example, JICA is working on Ho Chi Minh City’s first metro line and supports the training of the required workforce. The costs of these measurements are covered by the Japanese government’s financial aid. Establishing an operational base and perfecting all related mechanisms takes a lot of time. Therefore, the Vietnamese agencies also need to bear part of the financial burden. Together, both sides can maintain stability and expand the project’s achievements. So far, there have been many completed projects that were maintained and perfected by the Vietnamese side. I hope this will be the case for all our future cooperation. Although Vietnam managed to reduce the impact of the pandemic, it has not been completely unaffected. In my opinion, infrastructure development plays a crucial role in stimulating the economy. As ODA projects often aim at infrastructure, I hope that the government will take advantage of this kind of assistance. Finally, I hope the government will continue to work out further solutions to solve issues related to approval procedures and similar difficulties in project implementation. |